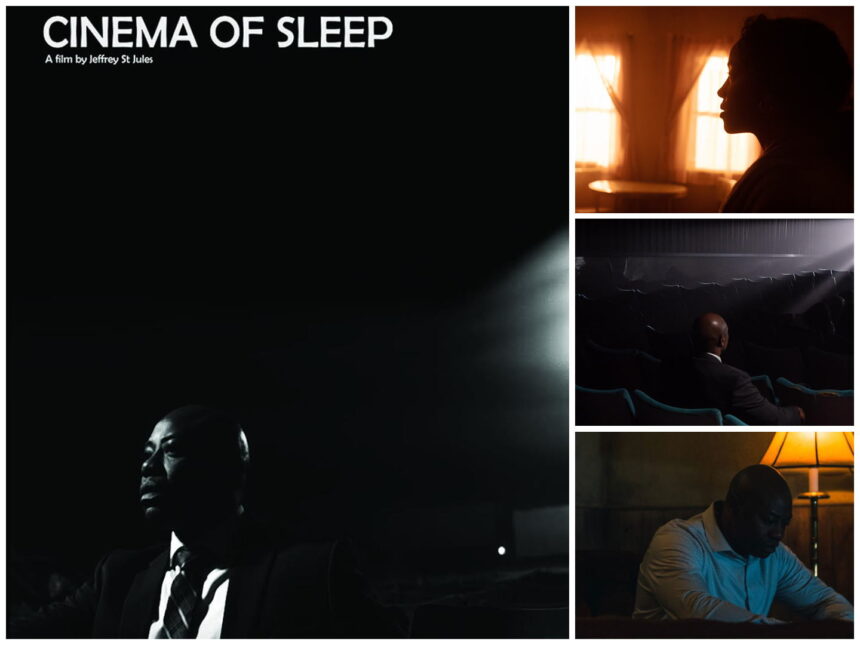

You'll either love this or hate it. Here's why:

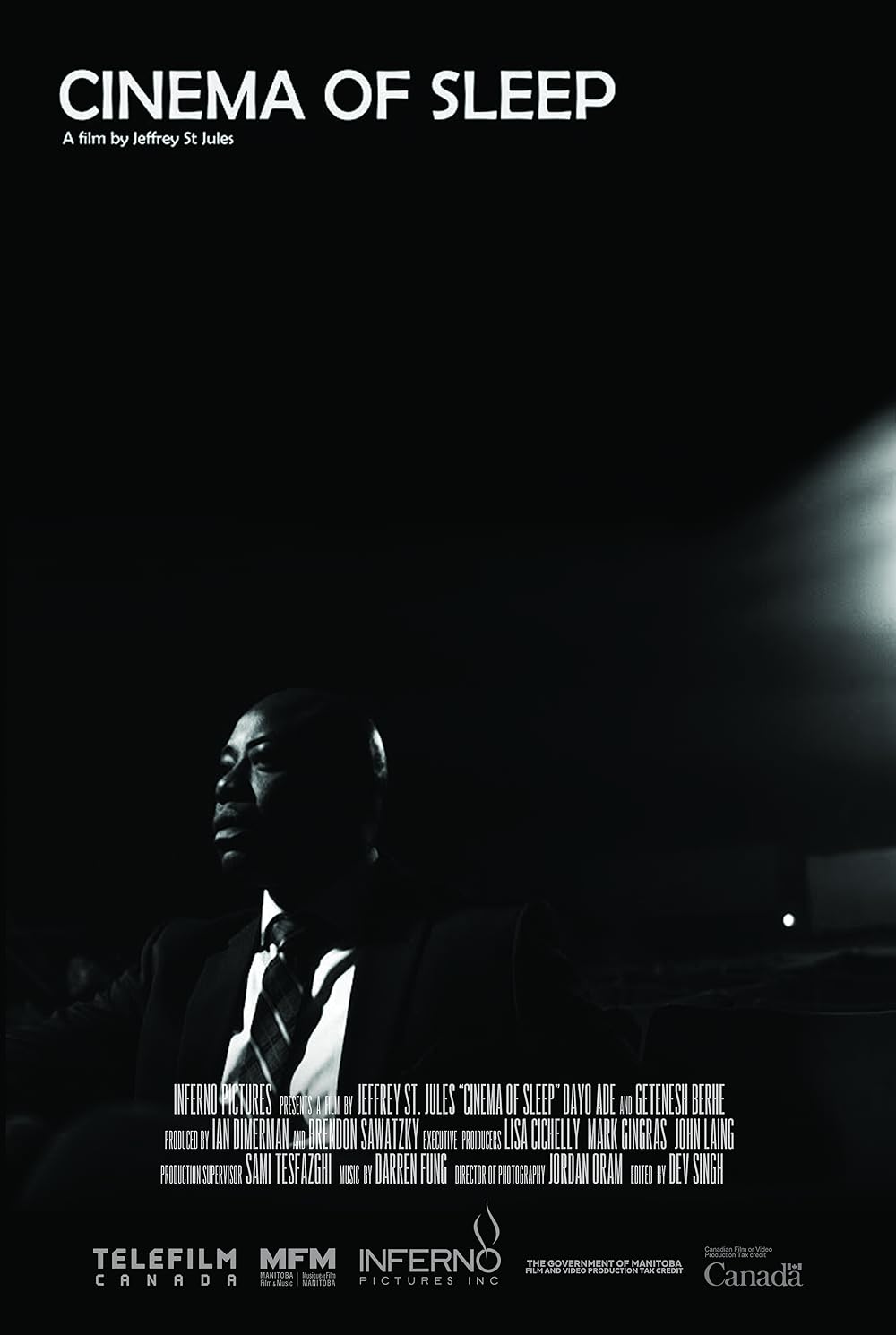

Cinema of Sleep is not your typical refugee drama. It doesn't ask politely for your empathy—it abducts your attention, sedates you with noir aesthetics, and then shakes you awake with a sucker-punch of surreal dread. Imagine The Twilight Zone had a baby with The Crying Game, then raised it on Hitchcock and Kafka. That's where we're at.

And here's the uncomfortable truth: Most films about refugees aim to educate. This one dares to confuse you first.

A Story That Breaks Its Own Rules

The premise is deceptively simple. A Nigerian refugee, Anthony (played with jaw-dropping nuance by Dayo Ade), wakes up in a motel room next to a dead woman. Not his wife. Not a stranger, exactly. More like… a cipher. Her name is Abrihet (Getenesh Berhe, riveting as a ghost wrapped in flesh), and the more Anthony tries to understand what happened, the more reality folds in on itself.

It's noir—but laced with dread, displacement, and dream logic. Director Jeffrey St. Jules doesn't just flirt with ambiguity—he proposes marriage to it.

Why This Isn't Just “Another Refugee Film”

A lot of refugee-centered narratives focus on trauma. Worthy, yes. Predictable, often. But Cinema of Sleep pulls a genre heist. It uses film noir—a style known for morally grey men, femmes fatales, and shadows that lie louder than the characters—to tell a story about people society prefers to keep in the dark.

Tanya Lapointe (EP of Dune) called it “a journey into the human soul.” She's not wrong. But it's more than that. This is genre cinema weaponized. The humanitarian crisis becomes a narrative glitch. We're not just watching Anthony survive—we're decoding his very sanity.

Maggie Lee from Variety nailed it: “It's an homage to film classics that cinephiles will love.” And yet it doesn't worship the past—it dismembers it, then reanimates it.

A Motel Room That Feels Like the Universe

Visually, the film is sparse. One location. Few characters. But as St. Jules explains, what's offscreen is “epic.” The motel room is liminal space—a floating purgatory between hope and horror. Kind of like what it feels like to seek asylum, maybe?

It's a brilliant inversion: the more contained the setting, the more uncontainable the meaning.

And Ade? He kills. ACTRA called his performance “flawless.” That might be underselling it. He doesn't just act—he dissolves into the role. You believe him because you feel him.

Don't Sleep on This Film

Awards? Racked up.

Whistler Film Festival: Best Canadian Feature, Best Performance (Ade), Jury praise that reads like poetry.

Charlottetown, Skip City, Canadian Screen nods for editing, music, and more.

Berhe even snagged an honorable mention that feels more like a silent scream.

So why hasn't everyone seen this?

Because it's not easy. Cinema of Sleep doesn't walk you through its message—it shoves you into it, blindfolded. And in a media landscape addicted to algorithmic clarity, that's radical.

So, would you risk your sense of reality for a story that actually means something?

Because that's what this film demands. Not just your attention—but your discomfort.

Go ahead. Press play. And try not to dream too hard.